Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Iron

Iron is an important component of good health. Detailed information on iron intake, iron deficiency and iron supplements.

Table of Contents

- Iron: What is it?

- What foods provide iron?

- What affects iron absorption?

- What is the recommended intake for iron?

- When can iron deficiency occur?

- Who may need extra iron to prevent a deficiency?

- Does pregnancy increase the need for iron?

- Some facts about iron supplements

- Who should be cautious about taking iron supplements?

- What are some current issues and controversies about iron?

- What is the risk of iron toxicity?

- Selecting a healthful diet

- References

Iron: What is it?

Iron, one of the most abundant metals on Earth, is essential to most life forms and to normal human physiology. Iron is an integral part of many proteins and enzymes that maintain good health. In humans, iron is an essential component of proteins involved in oxygen transport [1,2]. It is also essential for the regulation of cell growth and differentiation [3,4]. A deficiency of iron limits oxygen delivery to cells, resulting in fatigue, poor work performance, and decreased immunity [1,5-6]. On the other hand, excess amounts of iron can result in toxicity and even death [7].

Almost two-thirds of iron in the body is found in hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to tissues. Smaller amounts of iron are found in myoglobin, a protein that helps supply oxygen to muscle, and in enzymes that assist biochemical reactions. Iron is also found in proteins that store iron for future needs and that transport iron in blood. Iron stores are regulated by intestinal iron absorption [1,8].

What foods provide iron?

There are two forms of dietary iron: heme and nonheme. Heme iron is derived from hemoglobin, the protein in red blood cells that delivers oxygen to cells. Heme iron is found in animal foods that originally contained hemoglobin, such as red meats, fish, and poultry. Iron in plant foods such as lentils and beans is arranged in a chemical structure called nonheme iron [9]. This is the form of iron added to iron-enriched and iron-fortified foods. Heme iron is absorbed better than nonheme iron, but most dietary iron is nonheme iron [8]. A variety of heme and nonheme sources of iron are listed in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1: Selected Food Sources of Heme Iron [10]

| Food | Milligrams per serving | % DV* |

|---|---|---|

| Chicken liver, cooked, 3 ½ ounces | 12.8 | 70 |

| Oysters, breaded and fried, 6 pieces | 4.5 | 25 |

| Beef, chuck, lean only, braised, 3 ounces | 3.2 | 20 |

| Clams, breaded, fried, ¾ cup | 3.0 | 15 |

| Beef, tenderloin, roasted, 3 ounces | 3.0 | 15 |

| Turkey, dark meat, roasted, 3 ½ ounces | 2.3 | 10 |

| Beef, eye of round, roasted, 3 ounces | 2.2 | 10 |

| Turkey, light meat, roasted, 3 ½ ounces | 1.6 | 8 |

| Chicken, leg, meat only, roasted, 3 ½ ounces | 1.3 | 6 |

| Tuna, fresh bluefin, cooked, dry heat, 3 ounces | 1.1 | 6 |

| Chicken, breast, roasted, 3 ounces | 1.1 | 6 |

| Halibut, cooked, dry heat, 3 ounces | 0.9 | 6 |

| Crab, blue crab, cooked, moist heat, 3 ounces | 0.8 | 4 |

| Pork, loin, broiled, 3 ounces | 0.8 | 4 |

| Tuna, white, canned in water, 3 ounces | 0.8 | 4 |

| Shrimp, mixed species, cooked, moist heat, 4 large | 0.7 | 4 |

Table 2: Selected Food Sources of Nonheme Iron [10]

| Food | Milligrams per serving | % DV* |

|---|---|---|

| Ready-to-eat cereal, 100% iron fortified, ¾ cup | 18.0 | 100 |

| Oatmeal, instant, fortified, prepared with water, 1 cup | 10.0 | 60 |

| Soybeans, mature, boiled, 1 cup | 8.8 | 50 |

| Lentils, boiled, 1 cup | 6.6 | 35 |

| Beans, kidney, mature, boiled, 1 cup | 5.2 | 25 |

| Beans, lima, large, mature, boiled, 1 cup | 4.5 | 25 |

| Beans, navy, mature, boiled, 1 cup | 4.5 | 25 |

| Ready-to-eat cereal, 25% iron fortified, ¾ cup | 4.5 | 25 |

| Beans, black, mature, boiled, 1 cup | 3.6 | 20 |

| Beans, pinto, mature, boiled, 1 cup | 3.6 | 20 |

| Molasses, blackstrap, 1 tablespoon | 3.5 | 20 |

| Tofu, raw, firm, ½ cup | 3.4 | 20 |

| Spinach, boiled, drained, ½ cup | 3.2 | 20 |

| Spinach, canned, drained solids ½ cup | 2.5 | 10 |

| Black-eyed peas (cowpeas), boiled, 1 cup | 1.8 | 10 |

| Spinach, frozen, chopped, boiled ½ cup | 1.9 | 10 |

| Grits, white, enriched, quick, prepared with water, 1 cup | 1.5 | 8 |

| Raisins, seedless, packed, ½ cup | 1.5 | 8 |

| Whole wheat bread, 1 slice | 0.9 | 6 |

| White bread, enriched, 1 slice | 0.9 | 6 |

*DV = Daily Value. DVs are reference numbers developed by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to help consumers determine if a food contains a lot or a little of a specific nutrient. The FDA requires all food labels to include the percent DV (%DV) for iron. The percent DV tells you what percent of the DV is provided in one serving. The DV for iron is 18 milligrams (mg). A food providing 5% of the DV or less is a low source while a food that provides 10-19% of the DV is a good source. A food that provides 20% or more of the DV is high in that nutrient. It is important to remember that foods that provide lower percentages of the DV also contribute to a healthful diet. For foods not listed in this table, please refer to the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Nutrient Database Web site: http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/cgi-bin/nut_search.pl.

What affects iron absorption?

Iron absorption refers to the amount of dietary iron that the body obtains and uses from food. Healthy adults absorb about 10% to 15% of dietary iron, but individual absorption is influenced by several factors [1,3,8,11-15].

Storage levels of iron have the greatest influence on iron absorption. Iron absorption increases when body stores are low. When iron stores are high, absorption decreases to help protect against toxic effects of iron overload [1,3]. Iron absorption is also influenced by the type of dietary iron consumed. Absorption of heme iron from meat proteins is efficient. Absorption of heme iron ranges from 15% to 35%, and is not significantly affected by diet [15]. In contrast, 2% to 20% of nonheme iron in plant foods such as rice, maize, black beans, soybeans and wheat is absorbed [16]. Nonheme iron absorption is significantly influenced by various food components [1,3,11-15].

Meat proteins and vitamin C will improve the absorption of nonheme iron [1,17-18]. Tannins (found in tea), calcium, polyphenols, and phytates (found in legumes and whole grains) can decrease absorption of nonheme iron [1,19-24]. Some proteins found in soybeans also inhibit nonheme iron absorption [1,25]. It is most important to include foods that enhance nonheme iron absorption when daily iron intake is less than recommended, when iron losses are high (which may occur with heavy menstrual losses), when iron requirements are high (as in pregnancy), and when only vegetarian nonheme sources of iron are consumed.

What is the recommended intake for iron?

Recommendations for iron are provided in the Dietary Reference Intakes (DRIs) developed by the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences [1]. Dietary Reference Intakes is the general term for a set of reference values used for planning and assessing nutrient intake for healthy people. Three important types of reference values included in the DRIs are Recommended Dietary Allowances (RDA), Adequate Intakes (AI), and Tolerable Upper Intake Levels (UL). The RDA recommends the average daily intake that is sufficient to meet the nutrient requirements of nearly all (97-98%) healthy individuals in each age and gender group [1]. An AI is set when there is insufficient scientific data available to establish a RDA. AIs meet or exceed the amount needed to maintain a nutritional state of adequacy in nearly all members of a specific age and gender group. The UL, on the other hand, is the maximum daily intake unlikely to result in adverse health effects [1]. Table 3 lists the RDAs for iron, in milligrams, for infants, children and adults.

Table 3: Recommended Dietary Allowances for Iron for Infants (7 to 12 months), Children, and Adults [1]

| Age | Males (mg/day) | Females (mg/day) | Pregnancy (mg/day) | Lactation (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 to 12 months | 11 | 11 | N/A | N/A |

| 1 to 3 years | 7 | 7 | N/A | N/A |

| 4 to 8 years | 10 | 10 | N/A | N/A |

| 9 to 13 years | 8 | 8 | N/A | N/A |

| 14 to 18 years | 11 | 15 | 27 | 10 |

| 19 to 50 years | 8 | 18 | 27 | 9 |

| 51+ years | 8 | 8 | N/A | N/A |

Healthy full term infants are born with a supply of iron that lasts for 4 to 6 months. There is not enough evidence available to establish a RDA for iron for infants from birth through 6 months of age. Recommended iron intake for this age group is based on an Adequate Intake (AI) that reflects the average iron intake of healthy infants fed breast milk [1]. Table 4 lists the AI for iron, in milligrams, for infants up to 6 months of age.

Table 4: Adequate Intake for Iron for Infants (0 to 6 months) [1]

| Age (months) | Males and Females (mg/day) |

|---|---|

| 0 to 6 | 0.27 |

Iron in human breast milk is well absorbed by infants. It is estimated that infants can use greater than 50% of the iron in breast milk as compared to less than 12% of the iron in infant formula [1]. The amount of iron in cow's milk is low, and infants poorly absorb it. Feeding cow's milk to infants also may result in gastrointestinal bleeding. For these reasons, cow's milk should not be fed to infants until they are at least 1 year old [1]. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that infants be exclusively breast fed for the first six months of life. Gradual introduction of iron-enriched solid foods should complement breast milk from 7 to 12 months of age [26]. Infants weaned from breast milk before 12 months of age should receive iron-fortified infant formula [26]. Infant formulas that contain from 4 to 12 milligrams of iron per liter are considered iron-fortified [27].

Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) describe dietary intake of Americans 2 months of age and older. NHANES (1988-94) data suggest that males of all racial and ethnic groups consume recommended amounts of iron. However, iron intakes are generally low in females of childbearing age and young children [28-29].

Researchers also examine specific groups within the NHANES population. For example, researchers have compared dietary intakes of adults who consider themselves to be food insufficient (and therefore have limited access to nutritionally adequate foods) to those who are food sufficient (and have easy access to food). Older adults from food insufficient families had significantly lower intakes of iron than older adults who are food sufficient. In one survey, twenty percent of adults age 20 to 59 and 13.6% of adults age 60 and older from food insufficient families consumed less than 50% of the RDA for iron, as compared to 13% of adults age 20 to 50 and 2.5% of adults age 60 and older from food sufficient families [30].

Iron intake is negatively influenced by low nutrient density foods, which are high in calories but low in vitamins and minerals. Sugar sweetened sodas and most desserts are examples of low nutrient density foods, as are snack foods such as potato chips. Among almost 5,000 children and adolescents between the ages of 8 and 18 who were surveyed, low nutrient density foods contributed almost 30% of daily caloric intake, with sweeteners and desserts jointly accounting for almost 25% of caloric intake. Those children and adolescents who consumed fewer "low nutrient density" foods were more likely to consume recommended amounts of iron [31].

Data from The Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals (CSFII1994-6 and 1998) was used to examine the effect of major food and beverage sources of added sugars on micronutrient intake of U.S. children aged 6 to 17 years. Researchers found that consumption of presweetened cereals, which are fortified with iron, increased the likelihood of meeting recommendations for iron intake. On the other hand, as intake of sugar-sweetened beverages, sugars, sweets, and sweetened grains increased, children were less likely to consume recommended amounts of iron [32].

When can iron deficiency occur?

The World Health Organization considers iron deficiency the number one nutritional disorder in the world [33]. As many as 80% of the world's population may be iron deficient, while 30% may have iron deficiency anemia [34].

Iron deficiency develops gradually and usually begins with a negative iron balance, when iron intake does not meet the daily need for dietary iron. This negative balance initially depletes the storage form of iron while the blood hemoglobin level, a marker of iron status, remains normal. Iron deficiency anemia is an advanced stage of iron depletion. It occurs when storage sites of iron are deficient and blood levels of iron cannot meet daily needs. Blood hemoglobin levels are below normal with iron deficiency anemia [1].

Iron deficiency anemia can be associated with low dietary intake of iron, inadequate absorption of iron, or excessive blood loss [1,16,35]. Women of childbearing age, pregnant women, preterm and low birth weight infants, older infants and toddlers, and teenage girls are at greatest risk of developing iron deficiency anemia because they have the greatest need for iron [33]. Women with heavy menstrual losses can lose a significant amount of iron and are at considerable risk for iron deficiency [1,3]. Adult men and post-menopausal women lose very little iron, and have a low risk of iron deficiency.

Individuals with kidney failure, especially those being treated with dialysis, are at high risk for developing iron deficiency anemia. This is because their kidneys cannot create enough erythropoietin, a hormone needed to make red blood cells. Both iron and erythropoietin can be lost during kidney dialysis. Individuals who receive routine dialysis treatments usually need extra iron and synthetic erythropoietin to prevent iron deficiency [36-38].

Vitamin A helps mobilize iron from its storage sites, so a deficiency of vitamin A limits the body's ability to use stored iron. This results in an "apparent" iron deficiency because hemoglobin levels are low even though the body can maintain normal amounts of stored iron [39-40]. While uncommon in the U.S., this problem is seen in developing countries where vitamin A deficiency often occurs.

Chronic malabsorption can contribute to iron depletion and deficiency by limiting dietary iron absorption or by contributing to intestinal blood loss. Most iron is absorbed in the small intestines. Gastrointestinal disorders that result in inflammation of the small intestine may result in diarrhea, poor absorption of dietary iron, and iron depletion [41].

Signs of iron deficiency anemia include [1,5-6,42]:

- feeling tired and weak

- decreased work and school performance

- slow cognitive and social development during childhood

- difficulty maintaining body temperature

- decreased immune function, which increases susceptibility to infection

- glossitis (an inflamed tongue)

Eating nonnutritive substances such as dirt and clay, often referred to as pica or geophagia, is sometimes seen in persons with iron deficiency. There is disagreement about the cause of this association. Some researchers believe that these eating abnormalities may result in an iron deficiency. Other researchers believe that iron deficiency may somehow increase the likelihood of these eating problems [43-44].

People with chronic infectious, inflammatory, or malignant disorders such as arthritis and cancer may become anemic. However, the anemia that occurs with inflammatory disorders differs from iron deficiency anemia and may not respond to iron supplements [45-47]. Research suggests that inflammation may over-activate a protein involved in iron metabolism. This protein may inhibit iron absorption and reduce the amount of iron circulating in blood, resulting in anemia [48].

Who may need extra iron to prevent a deficiency?

Three groups of people are most likely to benefit from iron supplements: people with a greater need for iron, individuals who tend to lose more iron, and people who do not absorb iron normally. These individuals include [1,36-38,41,49-57]:

- pregnant women

- preterm and low birth weight infants

- older infants and toddlers

- teenage girls

- women of childbearing age, especially those with heavy menstrual losses

- people with renal failure, especially those undergoing routine dialysis

- people with gastrointestinal disorders who do not absorb iron normally

Celiac Disease and Crohn's Syndrome are associated with gastrointestinal malabsorption and may impair iron absorption. Iron supplementation may be needed if these conditions result in iron deficiency anemia [41].

Women taking oral contraceptives may experience less bleeding during their periods and have a lower risk of developing an iron deficiency. Women who use an intrauterine device (IUD) to prevent pregnancy may experience more bleeding and have a greater risk of developing an iron deficiency. If laboratory tests indicate iron deficiency anemia, iron supplements may be recommended.

Total dietary iron intake in vegetarian diets may meet recommended levels; however that iron is less available for absorption than in diets that include meat [58]. Vegetarians who exclude all animal products from their diet may need almost twice as much dietary iron each day as non-vegetarians because of the lower intestinal absorption of nonheme iron in plant foods [1]. Vegetarians should consider consuming nonheme iron sources together with a good source of vitamin C, such as citrus fruits, to improve the absorption of nonheme iron [1].

There are many causes of anemia, including iron deficiency. There are also several potential causes of iron deficiency. After a thorough evaluation, physicians can diagnose the cause of anemia and prescribe the appropriate treatment.

Does pregnancy increase the need for iron?

Nutrient requirements increase during pregnancy to support fetal growth and maternal health. Iron requirements of pregnant women are approximately double that of non-pregnant women because of increased blood volume during pregnancy, increased needs of the fetus, and blood losses that occur during delivery [16]. If iron intake does not meet increased requirements, iron deficiency anemia can occur. Iron deficiency anemia of pregnancy is responsible for significant morbidity, such as premature deliveries and giving birth to infants with low birth weight [1,51,59-62].

Low levels of hemoglobin and hematocrit may indicate iron deficiency. Hemoglobin is the protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen to tissues. Hematocrit is the proportion of whole blood that is made up of red blood cells. Nutritionists estimate that over half of pregnant women in the world may have hemoglobin levels consistent with iron deficiency. In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimated that 12% of all women age 12 to 49 years were iron deficient in 1999-2000. When broken down by groups, 10% of non-Hispanic white women, 22% of Mexican-American women, and 19% of non-Hispanic black women were iron deficient. Prevalence of iron deficiency anemia among lower income pregnant women has remained the same, at about 30%, since the 1980s [63].

The RDA for iron for pregnant women increases to 27 mg per day. Unfortunately, data from the 1988-94 NHANES survey suggested that the median iron intake among pregnant women was approximately 15 mg per day [1]. When median iron intake is less than the RDA, more than half of the group consumes less iron than is recommended each day.

Several major health organizations recommend iron supplementation during pregnancy to help pregnant women meet their iron requirements. The CDC recommends routine low-dose iron supplementation (30 mg/day) for all pregnant women, beginning at the first prenatal visit [33]. When a low hemoglobin or hematocrit is confirmed by repeat testing, the CDC recommends larger doses of supplemental iron. The Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences also supports iron supplementation during pregnancy [1]. Obstetricians often monitor the need for iron supplementation during pregnancy and provide individualized recommendations to pregnant women.

Some facts about iron supplements

Iron supplementation is indicated when diet alone cannot restore deficient iron levels to normal within an acceptable timeframe. Supplements are especially important when an individual is experiencing clinical symptoms of iron deficiency anemia. The goals of providing oral iron supplements are to supply sufficient iron to restore normal storage levels of iron and to replenish hemoglobin deficits. When hemoglobin levels are below normal, physicians often measure serum ferritin, the storage form of iron. A serum ferritin level less than or equal to 15 micrograms per liter confirms iron deficiency anemia in women, and suggests a possible need for iron supplementation [33].

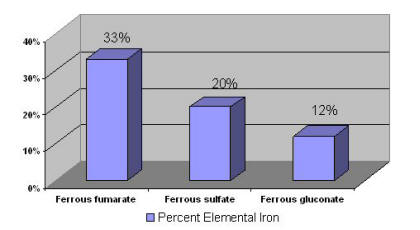

Supplemental iron is available in two forms: ferrous and ferric. Ferrous iron salts (ferrous fumarate, ferrous sulfate, and ferrous gluconate) are the best absorbed forms of iron supplements [64]. Elemental iron is the amount of iron in a supplement that is available for absorption. Figure 1 lists the percent elemental iron in these supplements.

Figure 1: Percent Elemental Iron in Iron Supplements [65]

The amount of iron absorbed decreases with increasing doses. For this reason, it is recommended that most people take their prescribed daily iron supplement in two or three equally spaced doses. For adults who are not pregnant, the CDC recommends taking 50 mg to 60 mg of oral elemental iron (the approximate amount of elemental iron in one 300 mg tablet of ferrous sulfate) twice daily for three months for the therapeutic treatment of iron deficiency anemia [33]. However, physicians evaluate each person individually, and prescribe according to individual needs.

Therapeutic doses of iron supplements, which are prescribed for iron deficiency anemia, may cause gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, dark colored stools, and/or abdominal distress [33]. Starting with half the recommended dose and gradually increasing to the full dose will help minimize these side effects. Taking the supplement in divided doses and with food also may help limit these symptoms. Iron from enteric coated or delayed-release preparations may have fewer side effects, but is not as well absorbed and not usually recommended [64].

Physicians monitor the effectiveness of iron supplements by measuring laboratory indices, including reticulocyte count (levels of newly formed red blood cells), hemoglobin levels, and ferritin levels. In the presence of anemia, reticulocyte counts will begin to rise after a few days of supplementation. Hemoglobin usually increases within 2 to 3 weeks of starting iron supplementation.

In rare situations parenteral iron (provided by injection or I.V.) is required. Doctors will carefully manage the administration of parenteral iron [66].

Who should be cautious about taking iron supplements?

Iron deficiency is uncommon among adult men and postmenopausal women. These individuals should only take iron supplements when prescribed by a physician because of their greater risk of iron overload. Iron overload is a condition in which excess iron is found in the blood and stored in organs such as the liver and heart. Iron overload is associated with several genetic diseases including hemochromatosis, which affects approximately 1 in 250 individuals of northern European descent [67]. Individuals with hemochromatosis absorb iron very efficiently, which can result in a build up of excess iron and can cause organ damage such as cirrhosis of the liver and heart failure [1,3,67-69]. Hemochromatosis is often not diagnosed until excess iron stores have damaged an organ. Iron supplementation may accelerate the effects of hemochromatosis, an important reason why adult men and postmenopausal women who are not iron deficient should avoid iron supplements. Individuals with blood disorders that require frequent blood transfusions are also at risk of iron overload and are usually advised to avoid iron supplements.

What are some current issues and controversies about iron?

Iron and heart disease:

Because known risk factors cannot explain all cases of heart disease, researchers continue to look for new causes. Some evidence suggests that iron can stimulate the activity of free radicals. Free radicals are natural by-products of oxygen metabolism that are associated with chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease. Free radicals may inflame and damage coronary arteries, the blood vessels that supply the heart muscle. This inflammation may contribute to the development of atherosclerosis, a condition characterized by partial or complete blockage of one or more coronary arteries. Other researchers suggest that iron may contribute to the oxidation of LDL ("bad") cholesterol, changing it to a form that is more damaging to coronary arteries.

As far back as the 1980s, some researchers suggested that the regular menstrual loss of iron, rather than a protective effect from estrogen, could better explain the lower incidence of heart disease seen in pre-menopausal women [70]. After menopause, a woman's risk of developing coronary heart disease increases along with her iron stores. Researchers have also observed lower rates of heart disease in populations with lower iron stores, such as those in developing countries [71-74]. In those geographic areas, lower iron stores are attributed to low meat (and iron) intake, high fiber diets that inhibit iron absorption, and gastrointestinal (GI) blood (and iron) loss due to parasitic infections.

In the 1980s, researchers linked high iron stores with increased risk of heart attacks in Finnish men [75]. However, more recent studies have not supported such an association [76-77].

One way of testing an association between iron stores and coronary heart disease is to compare levels of ferritin, the storage form of iron, to the degree of atherosclerosis in coronary arteries. In one study, researchers examined the relationship between ferritin levels and atherosclerosis in 100 men and women referred for cardiac examination. In this population, higher ferritin levels were not associated with an increased degree of atherosclerosis, as measured by angiography. Coronary angiography is a technique used to estimate the degree of blockage in coronary arteries [78]. In a different study, researchers found that ferritin levels were higher in male patients diagnosed with coronary artery disease. They did not find any association between ferritin levels and risk of coronary disease in women [79].

A second way to test this association is to examine rates of coronary disease in people who frequently donate blood. If excess iron stores contribute to heart disease, frequent blood donation could potentially lower heart disease rates because of the iron loss associated with blood donation. Over 2,000 men over age 39 and women over age 50 who donated blood between 1988 and 1990 were surveyed 10 years later to compare rates of cardiac events to frequency of blood donation. Cardiac events were defined as (1) occurrence of an acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), (2) undergoing angioplasty, a medical procedure that opens a blocked coronary artery; or (3) undergoing bypass grafting, a surgical procedure that replaces blocked coronary arteries with healthy blood vessels. Researchers found that frequent donors, who donated more than 1 unit of whole blood each year between 1988 and 1990, were less likely to experience cardiac events than casual donors (those who only donated a single unit in that 3-year period). Researchers concluded that frequent and long-term blood donation may decrease the risk of cardiac events [80].

Conflicting results, and different methods to measure iron stores, make it difficult to reach a final conclusion on this issue. However, researchers know that it is feasible to decrease iron stores in healthy individual through phlebotomy (blood letting or donation). Using phlebotomy, researchers hope to learn more about iron levels and cardiovascular disease.

Iron and intense exercise:

Many men and women who engage in regular, intense exercise such as jogging, competitive swimming, and cycling have marginal or inadequate iron status [1,81-85]. Possible explanations include increased gastrointestinal blood loss after running and a greater turnover of red blood cells. Also, red blood cells within the foot can rupture while running. For these reasons, the need for iron may be 30% greater in those who engage in regular intense exercise [1].

Three groups of athletes may be at greatest risk of iron depletion and deficiency: female athletes, distance runners, and vegetarian athletes. It is particularly important for members of these groups to consume recommended amounts of iron and to pay attention to dietary factors that enhance iron absorption. If appropriate nutrition intervention does not promote normal iron status, iron supplementation may be indicated. In one study of female swimmers, researchers found that supplementation with 125 milligrams (mg) of ferrous sulfate per day prevented iron depletion. These swimmers maintained adequate iron stores, and did not experience the gastrointestinal side effects often seen with higher doses of iron supplementation [86].

Iron and mineral interactions

Some researchers have raised concerns about interactions between iron, zinc, and calcium. When iron and zinc supplements are given together in a water solution and without food, greater doses of iron may decrease zinc absorption. However, the effect of supplemental iron on zinc absorption does not appear to be significant when supplements are consumed with food [1,87-88]. There is evidence that calcium from supplements and dairy foods may inhibit iron absorption, but it has been very difficult to distinguish between the effects of calcium on iron absorption versus other inhibitory factors such as phytate [1].

What is the risk of iron toxicity?

There is considerable potential for iron toxicity because very little iron is excreted from the body. Thus, iron can accumulate in body tissues and organs when normal storage sites are full. For example, people with hemachromatosis are at risk of developing iron toxicity because of their high iron stores.

In children, death has occurred from ingesting 200 mg of iron [7]. It is important to keep iron supplements tightly capped and away from children's reach. Any time excessive iron intake is suspected, immediately call your physician or Poison Control Center, or visit your local emergency room. Doses of iron prescribed for iron deficiency anemia in adults are associated with constipation, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, especially when the supplements are taken on an empty stomach [1].

In 2001, the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences set a tolerable upper intake level (UL) for iron for healthy people [1]. There may be times when a physician prescribes an intake higher than the upper limit, such as when individuals with iron deficiency anemia need higher doses to replenish their iron stores. Table 5 lists the ULs for healthy adults, children, and infants 7 to 12 months of age [1].

Table 5: Tolerable Upper Intake Levels for Iron for Infants 7 to 12 months, Children, and Adults [1]

| Age | Males (mg/day) | Females (mg/day) | Pregnancy (mg/day) | Lactation (mg/day) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 7 to 12 months | 40 | 40 | N/A | N/A |

| 1 to 13 years | 40 | 40 | N/A | N/A |

| 14 to 18 years | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

| 19 + years | 45 | 45 | 45 | 45 |

Selecting a healthful diet

As the 2000 Dietary Guidelines for Americans states, "Different foods contain different nutrients and other healthful substances. No single food can supply all the nutrients in the amounts you need" [89]. Beef and turkey are good sources of heme iron while beans and lentils are high in nonheme iron. In addition, many foods, such as ready-to-eat cereals, are fortified with iron. It is important for anyone who is considering taking an iron supplement to first consider whether their needs are being met by natural dietary sources of heme and nonheme iron and foods fortified with iron, and to discuss their potential need for iron supplements with their physician. If you want more information about building a healthful diet, refer to the Dietary Guidelines for Americans http://www.usda.gov/cnpp/DietGd.pdf [89], and the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Food Guide Pyramid http://www.usda.gov/cnpp/DietGd.pdf [90].

back to: Alternative Medicine Home ~ Alternative Medicine Treatments

References

- Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board. Dietary Reference Intakes for Vitamin A, Vitamin K, Arsenic, Boron, Chromium, Copper, Iodine, Iron, Manganese, Molybdenum, Nickel, Silicon, Vanadium and Zinc. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 2001.

- Dallman PR. Biochemical basis for the manifestations of iron deficiency. Annu Rev Nutr 1986;6:13-40. [PubMed abstract]

- Bothwell TH, Charlton RW, Cook JD, Finch CA. Iron Metabolism in Man. St. Louis: Oxford: Blackwell Scientific, 1979.

- Andrews NC. Disorders of iron metabolism. N Engl J Med 1999;341:1986-95. [PubMed abstract]

- Haas JD, Brownlie T 4th. Iron deficiency and reduced work capacity: a critical review of the research to determine a causal relationship. J Nutr 2001;131:691S-6S. [PubMed abstract]

- Bhaskaram P. Immunobiology of mild micronutrient deficiencies. Br J Nutr 2001;85:S75-80. [PubMed abstract]

- Corbett JV. Accidental poisoning with iron supplements. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs 1995;20:234. [PubMed abstract]

- Miret S, Simpson RJ, McKie AT. Physiology and molecular biology of dietary iron absorption. Annu Rev Nutr 2003;23:283-301.

- Hurrell RF. Preventing iron deficiency through food fortification. Nutr Rev 1997;55:210-22. [PubMed abstract]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. 2003. USDA Nutrient Database for Standard Reference, Release 16. Nutrient Data Laboratory Home Page, http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp.

- Uzel C and Conrad ME. Absorption of heme iron. Semin Hematol 1998;35:27-34. [PubMed abstract]

- Sandberg A. Bioavailability of minerals in legumes. British J of Nutrition. 2002;88:S281-5. [PubMed abstract]

- Davidsson L. Approaches to improve iron bioavailability from complementary foods. J Nutr 2003;133:1560S-2S. [PubMed abstract]

- Hallberg L, Hulten L, Gramatkovski E. Iron absorption from the whole diet in men: how effective is the regulation of iron absorption? Am J Clin Nutr 1997;66:347-56. [PubMed abstract]

- Monson ER. Iron and absorption: dietary factors which impact iron bioavailability. J Am Dietet Assoc. 1988;88:786-90.

- Tapiero H, Gate L, Tew KD. Iron: deficiencies and requirements. Biomed Pharmacother. 2001;55:324-32. [PubMed abstract]

- Hunt JR, Gallagher SK, Johnson LK. Effect of ascorbic acid on apparent iron absorption by women with low iron stores. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;59:1381-5. [PubMed abstract]

- Siegenberg D, Baynes RD, Bothwell TH, Macfarlane BJ, Lamparelli RD, Car NG, MacPhail P, Schmidt U, Tal A, Mayet F. Ascorbic acid prevents the dose-dependent inhibitory effects of polyphenols and phytates on nonheme-iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:537-41. [PubMed abstract]

- Samman S, Sandstrom B, Toft MB, Bukhave K, Jensen M, Sorensen SS, Hansen M. Green tea or rosemary extract added to foods reduces nonheme-iron absorption. Am J Clin Nutr 2001;73:607-12. [PubMed abstract]

- Brune M, Rossander L, Hallberg L. Iron absorption and phenolic compounds: importance of different phenolic structures. Eur J Clin Nutr 1989;43:547-57. [PubMed abstract]

- Hallberg L, Rossander-Hulthen L, Brune M, Gleerup A. Inhibition of haem-iron absorption in man by calcium. Br J Nutr 1993;69:533-40. [PubMed abstract]

- Hallberg L, Brune M, Erlandsson M, Sandberg AS, Rossander-Hulten L. Calcium: effect of different amounts on nonheme- and heme-iron absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1991;53:112-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Minihane AM, Fairweather-Tair SJ. Effect of calcium supplementation on daily nonheme-iron absorption and long-term iron status. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:96-102. [PubMed abstract]

- Cook JD, Reddy MB, Burri J, Juillerat MA, Hurrell RF. The influence of different cereal grains on iron absorption from infant cereal foods. Am J Clin Nutr 1997;65:964-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Lynch SR, Dassenko SA, Cook JD, Juillerat MA, Hurrell RF. Inhibitory effect of a soybean-protein-related moiety on iron absorption in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1994;60:567-72. [PubMed abstract]

- Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. American Academy of Pediatrics. Work Group on Breastfeeding. Pediatrics 1997;100:1035-9. [PubMed abstract]

- 27 American Academy of Pediatrics: Committee on Nutrition. Iron fortification of infant formulas. Pediatrics 1999;104:119-23. [PubMed abstract]

- Bialostosky K, Wright JD, Kennedy-Stephenson J, McDowell M, Johnson CL. Dietary intake of macronutrients, micronutrients and other dietary constituents: United States 1988-94. Vital Heath Stat. 11(245) ed: National Center for Health Statistics, 2002:168. [PubMed abstract]

- Interagency Board for Nutrition Monitoring and Related Research. Third Report on Nutrition Monitoring in the United States. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, J Nutr. 1996;126:iii-x: 1907S-36S.

- Dixon LB, Winkleby MA, Radimer KL. Dietary intakes and serum nutrients differ between adults from food insufficient and food sufficient families: Third National Health and Nutrition Examination. J Nutr 2001;131:1232-46. [PubMed abstract]

- Kant A. Reported consumption of low-nutrient-density foods by American children and adolescents. Arch Pediatr Aolesc Med 1993;157:789-96

- Frary CD, Johnson RK, Wang MQ. Children and adolescents' choice of foods and beverages high in added sugars are associated with intakes of key nutrients and food groups. J Adolesc Health 2004;34:56-63. [PubMed abstract]

- CDC Recommendations to prevent and control iron deficiency in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep 1998;47:1-29.

- Stoltzfus RJ. Defining iron-deficiency anemia in public health terms: reexamining the nature and magnitude of the public health problem. J Nutr 2001;131:565S-7S.

- Hallberg L. Prevention of iron deficiency. Baillieres Clin Haematol 1994;7:805-14. [PubMed abstract]

- Nissenson AR, Strobos J. Iron deficiency in patients with renal failure. Kidney Int Suppl 1999;69:S18-21. [PubMed abstract]

- Fishbane S, Mittal SK, Maesaka JK. Beneficial effects of iron therapy in renal failure patients on hemodialysis. Kidney Int Suppl 1999;69:S67-70. [PubMed abstract]

- Drueke TB, Barany P, Cazzola M, Eschbach JW, Grutzmacher P, Kaltwasser JP, MacDougall IC, Pippard MJ, Shaldon S, van Wyck D. Management of iron deficiency in renal anemia: guidelines for the optimal therapeutic approach in erythropoietin-treated patients. Clin Nephrol 1997;48:1-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Kolsteren P, Rahman SR, Hilderbrand K, Diniz A. Treatment for iron deficiency anaemia with a combined supplementation of iron, vitamin A and zinc in women of Dinajpur, Bangladesh. Eur J Clin Nutr 1999;53:102-6. [PubMed abstract]

- van Stuijvenberg ME, Kruger M, Badenhorst CJ, Mansvelt EP, Laubscher JA. Response to an iron fortification programme in relation to vitamin A status in 6-12-year-old school children. Int J Food Sci Nutr 1997;48:41-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Annibale B, Capurso G, Chistolini A, D'Ambra G, DiGiulio E, Monarca B, DelleFave G. Gastrointestinal causes of refractory iron deficiency anemia in patients without gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Med 2001;111:439-45. [PubMed abstract]

- Allen LH, Iron supplements: scientific issues concerning efficacy and implications for research and programs. J Nutr 2002;132:813S-9S. [PubMed abstract]

- Rose EA, Porcerelli JH, Neale AV. Pica: common but commonly missed. J Am Board Fam Pract 2000;13:353-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Singhi S, Ravishanker R, Singhi P, Nath R. Low plasma zinc and iron in pica. Indian J Pediatr 2003;70:139-43. [PubMed abstract]

- Jurado RL. Iron, infections, and anemia of inflammation. Clin Infect Dis 1997;25:888-95. [PubMed abstract]

- Abramson SD, Abramson N. 'Common' uncommon anemias. Am Fam Physician 1999;59:851-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Spivak JL. Iron and the anemia of chronic disease. Oncology (Huntingt) 2002;16:25-33. [PubMed abstract]

- Leong W and Lonnerdal B. Hepcidin, the recently identified peptide that appears to regulate iron absorption. J Nutr 2004;134:1-4. [PubMed abstract]

- Picciano MF. Pregnancy and lactation: physiological adjustments, nutritional requirements and the role of dietary supplements. J Nutr 2003;133:1997S-2002S. [PubMed abstract]

- Blot I, Diallo D, Tchernia G. Iron deficiency in pregnancy: effects on the newborn. Curr Opin Hematol 1999;6:65-70. [PubMed abstract]

- Cogswell ME, Parvanta I, Ickes L, Yip R, Brittenham GM. Iron supplementation during pregnancy, anemia, and birth weight: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:773-81. [PubMed abstract]

- Idjradinata P, Pollitt E. Reversal of developmental delays in iron-deficient anaemic infants treated with iron. Lancet 1993;341:1-4. [PubMed abstract]

- Bodnar LM, Cogswell ME, Scanlon KS. Low income postpartum women are at risk of iron deficiency. J Nutr 2002;132:2298-302. [PubMed abstract]

- Looker AC, Dallman PR, Carroll MD, Gunter EW, Johnson CL. Prevalence of iron deficiency in the United States. J Am Med Assoc 1997;277:973-6. [PubMed abstract]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Nutrition 2003-2004. Pediatric Nutrition Handbook, 5th edition. 2004. Ch 19: Iron Deficiency. p 299-312.

- Bickford AK. Evaluation and treatment of iron deficiency in patients with kidney disease. Nutr Clin Care 2002;5:225-30. [PubMed abstract]

- Canavese C, Bergamo D, Ciccone G, Burdese M, Maddalena E, Barbieri S, Thea A, Fop F. Low-dose continuous iron therapy leads to a positive iron balance and decreased serum transferrin levels. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004;19:1564-70. [PubMed abstract]

- Hunt JR. Bioavailability of iron, zinc, and other trace minerals from vegetarian diets. Am J Clin Nutr 2003;78:633S-9S. [PubMed abstract]

- Blot I, Diallo D, Tchernia G. Iron deficiency in pregnancy: effects on the newborn. Curr Opin Hematol 1999;6:65-70. [PubMed abstract]

- Malhotra M, Sharma JB, Batra S, Sharma S, Murthy NS, Arora R. Maternal and perinatal outcome in varying degrees of anemia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2002;79:93-100. [PubMed abstract]

- Allen LH. Pregnancy and iron deficiency: unresolved issues. Nutr Rev 1997;55:91-101. [PubMed abstract]

- Iron deficiency anemia: recommended guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management among U.S. children and women of childbearing age. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine. Food and Nutrition Board.National Academy Press, 1993.

- Cogswell ME, Kettel-Khan L, Ramakrishnan U. Iron supplement use among women in the United States: science, policy and practice. J Nutr 2003:133:1974S-7S. [PubMed abstract]

- Hoffman R, Benz E, Shattil S, Furie B, Cohen H, Silberstein L, McGlave P. Hematology: Basic Principles and Practice, 3rd ed. ch 26: Disorders of Iron Metabolism: Iron deficiency and overload. Churchill Livingstone, Harcourt Brace & Co, New York, 2000.

- Drug Facts and Comparisons. St. Louis: Facts and Comparisons, 2004.

- Kumpf VJ. Parenteral iron supplementation. Nutr Clin Pract 1996;11:139-46. [PubMed abstract]

- Burke W, Cogswell ME, McDonnell SM, Franks A. Public Health Strategies to Prevent the Complications of Hemochromatosis. Genetics and Public Health in the 21st Centry: using genetic information to improve health and prevent disease. Oxford University Press, 2000.

- Bothwell TH, MacPhail AP. Hereditary hemochromatosis: etiologic, pathologic, and clinical aspects. Semin Hematol 1998;35:55-71. [PubMed abstract]

- Brittenham GM. New advances in iron metabolism, iron deficiency, and iron overload. Curr Opin Hematol 1994;1:101-6. [PubMed abstract]

- Sullivan JL. Iron versus cholesterol--perspectives on the iron and heart disease debate. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1345-52. [PubMed abstract]

- Weintraub WS, Wenger NK, Parthasarathy S, Brown WV. Hyperlipidemia versus iron overload and coronary artery disease: yet more arguments on the cholesterol debate. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1353-8. [PubMed abstract]

- Sullivan JL. Iron versus cholesterol--response to dissent by Weintraub et al. J Clin Epidemiol 1996;49:1359-62. [PubMed abstract]

- Sullivan JL. Iron therapy and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Int Suppl 1999;69:S135-7. [PubMed abstract]

- Salonen JT, Nyyssonen K, Korpela H, Tuomilehto J, Seppanen R, Salonen R. High stored iron levels are associated with excess risk of myocardial infarction in eastern Finnish men. Circulation 1992;86:803-11. [PubMed abstract]

- Sempos CT, Looker AC, Gillum RF, Makuc DM. Body iron stores and the risk of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 1994;330:1119-24. [PubMed abstract]

- Danesh J, Appleby P. Coronary heart disease and iron status: meta-analyses of prospective studies. Circulation 1999;99:852-4. [PubMed abstract]

- Ma J, Stampfer MJ. Body iron stores and coronary heart disease. Clin Chem 2002;48:601-3. [PubMed abstract]

- Auer J, Rammer M, Berent R, Weber T, Lassnig E, Eber B. Body iron stores and coronary atherosclerosis assessed by coronary angiography. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 2002;12:285-90. [PubMed abstract]

- Zacharski LR, Chow B, Lavori PW, Howes P, Bell M, DiTommaso M, Carnegie N, Bech F, Amidi M, Muluk S. The iron (Fe) and atherosclerosis study (FeAST): A pilot study of reduction of body iron stores in atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease. Am Heart J 2000;139:337-45. [PubMed abstract]

- Meyers DG, Jensen KC, Menitove JE. A historical cohort study of the effect of lowering body iron through blood donation on incident cardiac events. Transfusion. 2002;42:1135-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Clarkson PM and Haymes EM. Exercise and mineral status of athletes: calcium, magnesium, phosphorus, and iron. Med Sci Sports Exerc 1995;27:831-43. [PubMed abstract]

- Raunikar RA, Sabio H. Anemia in the adolescent athlete. Am J Dis Child 1992;146:1201-5. [PubMed abstract]

- Lampe JW, Slavin JL, Apple FS. Iron status of active women and the effect of running a marathon on bowel function and gastrointestinal blood loss. Int J Sports Med 1991;12:173-9. [PubMed abstract]

- Fogelholm M. Inadequate iron status in athletes: An exaggerated problem? Sports Nutrition: Minerals and Electrolytes. Boca Raton: CRC Press, 1995:81-95.

- Beard J and Tobin B. Iron status and exercise. Am J Clin Nutr 2000:72:594S-7S. [PubMed abstract]

- Brigham DE, Beard JL, Krimmel RS, Kenney WL. Changes in iron status during competitive season in female collegiate swimmers. Nutrition 1993;9:418-22. [PubMed abstract]

- Whittaker P. Iron and zinc interactions in humans. Am J Clin Nutr 1998;68:442S-6S. [PubMed abstract]

- Davidsson L, Almgren A, Sandstrom B, Hurrell RF. Zinc absorption in adult humans: the effect of iron fortification. Br J Nutr 1995;74:417-25. [PubMed abstract]

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Nutrition and Your Health: Dietary Guidelines for Americans. 5th ed. USDA Home and Garden Bulleting No. 232, Washington, DC: USDA, 2000. http://www.cnpp.usda.gov/DietaryGuidelines.htm

- Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion. United States Department of Agriculture. Food Guide Pyramid, 1992 (slightly revised 1996). http://www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/Fpyr/pyramid.htmll

DisclaimerReasonable care has been taken in preparing this document and the information provided herein is believed to be accurate. However, this information is not intended to constitute an "authoritative statement" under Food and Drug Administration rules and regulations.

About ODS and the NIH Clinical Center

The mission of the Office of Dietary Supplements (ODS) is to strengthen knowledge and understanding of dietary supplements by evaluating scientific information, stimulating and supporting research, disseminating research results, and educating the public to foster an enhanced quality of life and health for the U.S. population.

The NIH Clinical Center is the clinical research hospital for NIH. Through clinical research, physicians and scientist translate laboratory discoveries into better treatments, therapies and interventions to improve the nation's health.

General Safety Advisory

Health professionals and consumers need credible information to make thoughtful decisions about eating a healthful diet and using vitamin and mineral supplements. To help guide those decisions, registered dietitians at the NIH Clinical Center developed a series of Fact Sheets in conjunction with ODS. These Fact Sheets provide responsible information about the role of vitamins and minerals in health and disease. Each Fact Sheet in this series received extensive review by recognized experts from the academic and research communities.

The information is not intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice. It is important to seek the advice of a physician about any medical condition or symptom. It is also important to seek the advice of a physician, registered dietitian, pharmacist, or other qualified health professional about the appropriateness of taking dietary supplements and their potential interactions with medications.

back to: Alternative Medicine Home ~ Alternative Medicine Treatments

APA Reference

Staff, H.

(2008, November 18). Dietary Supplement Fact Sheet: Iron, HealthyPlace. Retrieved

on 2026, March 5 from https://www.healthyplace.com/alternative-mental-health/treatments/dietary-supplement-iron