This is a vulnerable admission for me to write, but my 15-year battle with an eating disorder has made an impact on my sexual desire. There—I confessed it openly. I pushed back against the shame, embarrassment, and insecurity that too often silences me on this particular issue.

Identity

For those of us who have or have had eating disorders, the feeling of a full stomach can be an extremely disconcerting sensation. Sitting after a meal while feeling full can cause anxiety and guilt. I've been in recovery for nearly a decade and I still sometimes struggle with feeling full, but learning how to be okay with being full was an important step in my eating disorder (ED) recovery.

I don't believe in eating disorder triggers. Sounds pretty bold, right? We live in a world awash with eating disorder (ED) trigger warnings and those of us who are in ED recovery are constantly warned to avoid our triggers lest we slip back into old habits, and I straight-up say I don't believe in them.

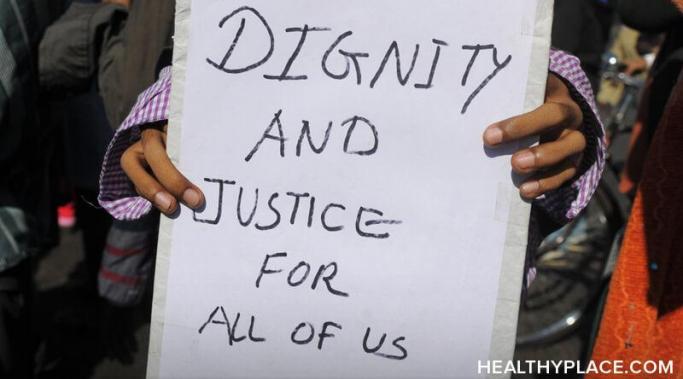

Social justice and eating disorder recovery are two of the driving forces in my life. It informs my relationships, conversations, and writing, but I cannot take credit for this—eating disorder recovery introduced me to social justice.

If you have dealt with any patterns of disordered eating in your life, chances are these behaviors were—or continue to be—fueled by negative self-talk around body image. Since the brain is a complex, independent, thinking organism, self-talk is an intrinsic part of the human experience. You are hardwired for internal dialog with yourself, and this is not always problematic. That endless stream-of-consciousness in your head is shaped by the beliefs, perspectives, attitudes, and observations that help you negotiate the world around you. When used constructively, self-talk can empower you to confront fears, gain motivation or discipline, boost confidence, and strengthen areas of improvement. But if this self-talk turns critical toward yourself—in particular, how you look or what you weigh—it causes shame to take root and harmful behaviors to manifest which could result in an eating disorder. So it's important to learn how to reframe your negative self-talk around body image into a kinder, more compassionate dialog.

The rate of eating disorders in the transgender community is an epidemic. While it has been estimated that over 30 million people in the United States alone suffer from eating disorders1, how many of these individuals conform to the heteronormative standards of body and gender—and how many don't? The research into this question is sparse, but there is enough to infer that eating disorders in the trans community are both epidemic and overlooked. While the archaic notion that eating disorders tend to primarily affect those who are female, white, and cisgender has been dismantled in recent years, the transgender population is still marginalized—or worse, excluded—from this conversation. Their stories of body-centric violence, trauma, prejudice, and exploitation have caused untold numbers of transgender people to fall into a cycle of disordered eating behaviors. But it's time society is made aware of these men and women in the transgender community who suffer—and recover—from eating disorders, so this epidemic will not be overlooked anymore.

There is a common—and dangerous—eating disorder stigma in society that says eating disorders result from vanity and a need for attention, but the truth is, eating disorders are not for the vain. This eating disorder stigma minimizes just how severe and catastrophic these illnesses can become while reinforcing the belief that sufferers cannot reach out for help, lest they be dismissed as attention-seekers fixated on their own appearance. But in order to dismantle this added layer of cultural stigma that keeps so many victims both silent and ashamed, it's important to realize that eating disorders are not for the vain. Rather, they are caused by intricate, nuanced factors that are often unrelated to vanity and rooted instead in trauma, self-loathing, or insecurity.

Culturally, eating disorders are often associated with young teenagers who don't know exactly how to cope with their developing bodies or fluctuating dynamics in their families and peer groups. But as teens become older and transition from high school to the broader world of a university campus, they can be even more susceptible to disordered eating behaviors. The risk of eating disorders in college students has continued to escalate these past several years, and there are multiple reasons behind the persistence of this issue.

What are the indicators that an eating disorder has led to suicidal ideation? Are there shifts in mood or patterns of behavior to look for in people who battle this disease? How common is suicide in the disordered eating population, and which signs need to be taken seriously as cries for help or intervention? (Note: This post contains a trigger warning.)

There have been countless moments during my time in both outpatient therapy and inpatient treatment when a certain fear held me back from embracing true recovery—the question, "Who am I without my eating disorder?" I knew the illness had starved my body, wrecked my relationships, consumed my mind, and seduced me into harmful decisions, but I clung to it still as my one source of identity. I was terrified of losing the behaviors that I assumed—inaccurately—made me both special and unique.